Rossika. A. Roslin, J.-L. Voal, V. Eriksen, S. Torelli, I. B. Lampi Senior, M.-E.-L. Vizhe-Labrene Rossika of the second half of the XVIII century. Against the backdrop of a mature and highly professional Russian school – already

Rossika. A. Roslin, J.-L. Voal, V. Eriksen, S. Torelli, I. B. Lampi Senior, M.-E.-L. Vizhe-Labrene

Rossika of the second half of the XVIII century. Against the backdrop of a mature and highly professional Russian school, it is no longer a model for imitation, as in Petrovskoe times, but a usual cooperation for all European schools. Moreover, among those who lived in Russia in Catherine's time, foreign painters and sculptors did not correspond to the talent of the F. S. Rokotov, D. G. Levitsky or V. L. Borovikovsky, nor M. I. Kozlovsky, F. I. Shubin, I.P. Martos or F.F. Shchedrin. The exception can be only M. E. Falcone, but it is significant that it was in Russia that this master created its best work. Equal forces were, as the researchers note, only in architecture, where the names of V. I. Bazhenov, M. I. Kazakov or I. E. Starov can be opposed to J.-B. Wallen-drama, C. Cameron or J. Quarengs.

Only one thing remains unchanged in Russian life – wages. In particular, from the documents it is clear that the annual salary of Lagren, who had arrived for a short time in Russia, was 2350 rubles. Despite the fact that the president of the Academy Shuvalov received 1000 rubles, and the teachers Golovachevsky and the Sablukov – 178 rubles each. Levitsky, whose glory rattled in the 1780s, received 2500 rubles for the portrait of the empress, and the elder lamp-12 thousand rubles. Examples can be continued.

In the second half of the century, French craftsmen Zh.-L. worked in Russia in Russia Denies, J.-L. Voal, A. Roslin, M.-E.-L. VIZH-LEBREN, J.-L. Monier; Italians S. Torelli, F. Fontebasso, S. Tonschi; Germans F. X. Barizen, G. Kugelgen; Austrians I. B. Lampi father and son. Everyone had their own customers, but basically it is the imperial court and know. Customers dictated their conditions, which unites all masters, but, of course, does not deprive them of an individual manner.

So, Alexander Roslin (Roslen, 1718–1793), a Swede in origin, who worked for a long time in Paris and therefore quite suitable for the definition of a representative of the French school, left the images of the Russian aristocracy full of vitality, gleaning the beauty of the costumes, the texture of velvet, silk, mand mosts and the posts of mand mosts in these portraits. sparkling orders (portrait of A. S. Stroganova, 1772, timing). Roslin did not condescend to idealization, which caused the empress’s discontent with her portrait (1776/1777, GE). She said about this image (and not without reason) that she looks like a “Swedish cook, very vulgar, badly educated and unsuccessful.” As for the vulgarity and bad manner, of course, it is difficult to judge by the portrait, but in general, a certain burgher note in the image is present. Roslin spent about two years in Russia (1775–1777).

Jean-Louis Voal (1744 – after 1803) lived in Russia much longer – about 30 years. He had a very defined customer here – the small courtyard of Pavel Petrovich and Maria Fedorovna, and in addition, two families – Stroganov and Pan. Of all the French masters, the veil is possibly closest to the Russian school: its images are spiritualized, full of internal movement, state of variability, dreaminess, sometimes melancholy, characteristic of both sentimentalism and the impending time of romanticism. The backgrounds of the portraits of the voila are usually neutral. Favorite gamma-silver-blue, silver-faced with pink. The paints are liquid, blurry, sometimes it is not believed that it is oil, not pastel or watercolor (portrait of S.V. Panina, 1791; portrait of N. P. Panin, 1792; both GTG). The veil is undoubtedly one of the most interesting artists of Rossika of this time. Its portraits are beautiful in color, subtly spiritualized. However, as the researchers note, in all its models there is something in common: the seal of inappropriate to the world, confusion, features of aristocratic loneliness, evidence of individualistic, pretentious worldview, a combination of physical well -being and spiritual instability (O. Evangulova Russian portrait of the XVIII century and the Russian portrait of the XVIII century and The problem of Russians // Art. 1986. No. 12. P. 60).

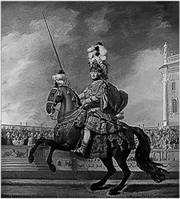

In addition to Roslin, more related to French art, the Scandinavian school in Russia was represented by the work of the Danish Wigilius Ericksen (1722–1782), who was educated at home, in Copenhagen. In 1757-1772 He lived in St. Petersburg, where at court, according to Y. Shtelin, was contained as the first court painter. Ericksen wrote portraits Cavaliers and ladies in their ceremonial vestments, the so -called carousel portraits, capturing Alexei and Grigory Orlovs in the costumes of Saracens and the Roman warrior (1766–1772, GE). He repeatedly wrote the empress in various portrait genres-from her most famous image in a large-based pompous portrait in the Preobrazhensky uniform on a horse (1762, Peterhof, a Great Palace) to almost chamber, in front of the mirror and even in the Russian style (Portrait of Catherine II in Shuga and Kokoshnik). Ericksen's skim portraits are written in such a light, transparent smear that they suggest the reminiscences of rockeral style.

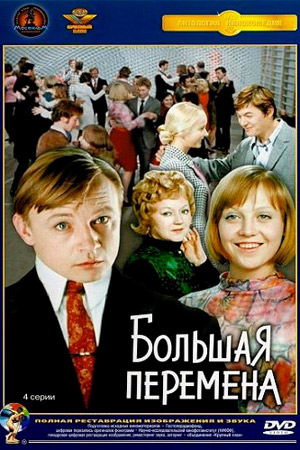

For a long time lived in Russia Stefano Torelli (1712–1780), who arrived in St. Petersburg at the age of 50, already a famous artist who has worked a lot in his homeland and in Germany as a wall -painter, a master of altar picture and portrait painters. In Russia, he mainly creates allegorical paintings and portraits in the pan -Hyric spirit of baroque academism: “Coroning of Catherine II on September 22, 1762” (1763, GTG; Vot. – Tsarskoye Selo Museum), “Catherine II in the image of Minerva, patroness of art” (1771, TM), Allegory for the victory of Priestine II over the Turks and Tatars (1772, GTG), Diana and Endimion (Chinese Palace in Oranienbaum).

The names of the canvases speak for themselves.These are large multi -figure compositions with skillful mise -en -scenes in which the artist did not escape the external beautifulness and effectiveness of writing. Oranienbaum murals, especially the plafond of the Musa Hall in the Chinese Palace, is the best creation of decorative painting Rococo in Russia, sophisticated, pampered, refined. However, this style is already in the past, and not only for Western Europe, but also for Russia (unnecessary proof of how quickly on Russian soil the assimilation of Western European principles, directions and picturesque techniques occurs).

V. Eriksen. A. G. Orlov in a suit of Saracens (left). 1766-1772, GE

G. G. Orlov in a costume of the Roman warrior (right). 1766-1772, GE

S. Torelli. Catherine II in the image of Minerva, the patroness of the arts. 1771, timing

In the 1790s. At the invitation of G. A. Potemkin to Russia (first to Yassy, and then to St. Petersburg), an Austrian painter arrived Johann Baptist Lamny Senior (1751–1830). The lamp was a huge success at the court, becoming truly the most fashionable portrait, who had managed to “rewrite” and the old Russian nobility in five years – the Kurakins, Yusupovs, Bezborodko, and the new, ascended to the highest stage of fame, which turned out to be “in case”. So, in the front portraits of Plato and Valerian Zubov (1796, timing), he creates a type of successful courtier, but all the arrogance and pride of the appearance of the models, transmitted by a brush of lightweight and impassive, with an amazing property of the lamp “beautifully flatter” – does not hide their insignificance. Especially this flattery is read in the portrait of Plato Zubov (crookedly chicken, according to the witty remark of one modern researcher), on which the ranks and orders were sprinkled after the death of Potemkin. Catherine, like a “homegrown Pygmalion,” wanted to create a new Potemkin from him: “He himself sought to imitate the deceased prince, but for this Plato Zubov had neither his abilities, no courage, nor mind, no kindness, nor wideness. But the last favorite had an abundance of arrogance, swagger, arrogance and powerfulness. Suvorov called him “crafty”, as you know, the people so call the feature ”(Sorotokina N. M. Favorites of Ekaterina Great., 2012. P. 270–271 ).

Pavel I, who had just entered the throne, attributes the words “they will pay for themselves”, who were told by him, upon refusal to pay for the portrait of Valerian Zubov. Such neglect is not even to the model itself, but it is difficult to imagine to the work of a foreign master in an earlier era, but the lamp was a European famous artist.

The art of a superficial and dexterous French artist was literally triumphant Marie-Luizo-Elizabeth Vizha-Labrene (1755–1842), court portrait of Maria Antoinette. Exilled from France by the revolution, Vizhe-Labrene is looking for a refuge in many European courtyards and finds it in Russia. Like the ladies of the senior, Vizhe-Labrene was a huge success at the court. The pragmatic and prudent, undoubtedly masterful and possessing good imagination, she sensitively caught in general the salon tastes of the court environment, knew how to please her.This was mixed with her lively active activity, the structure of costumed evenings, which became fashionable for “living paintings”, etc. And she often dresses her models in theatrical dresses, mixes with the “Oriental” details to the European costume (the Turitor which came into fashion, etc. .), beautifully dissolves the hair of his eminent female models. She also appears to be the same salon-beautiful in self-portraits, for example, in a “self-portrait with a daughter” (who later also “joined” art, but quickly forgot about him, marrying the secretary of Count Chernyshev, about which N. N. Wrangel He wrote maliciously that if it was a loss for his mother, then it was not a loss for art, judging by her two pastels, red and oblique). It is rightly noticed that a shade of sugary sensitivity borders in portraits of Vizha-Labrene on almost primitive sensuality.

Portraits of mothers with children are the favorite compositions of the artist. But if Borovikovsky’s theme of family virtue always receives a strict ampir form and, most importantly, a high moral basis, then Vizha-Light is always beautiful, sweet, touching, in general, completely salon image (portrait of A. S. Stroganova with his son Nikolai, 1793, he). “They were given sensuality, and the feeling was given to us,” wrote Evgeny Baratynsky, comparing Lawrence with Cyprus. Even to a greater extent, this could be said about Vizh-Labrene.

One way or another, the masters of the second half of the century came to Russia often at the end of their glory, and Russian masters could learn a lot from them, but to teach them a lot (more about foreigners in Russia see: O.S. Evangulova, Karev A. A. Portrait painting in Russia of the second half of the 18th century. M., 1994. [Ch. VI: Foreign portraitors in Russia (Rossika)]. P. 138–158).