Belarusian track and field athlete Kristina Timanovskaya, who refused to return to Minsk after the leaders of the national team suspended her from competitions at the Olympics in Tokyo, and turned to the police, asking for asylum, is far from the first athlete from the countries of the former USSR who entered …

From hockey to chess: which of the athletes fled to the West from the USSR and Russia and why

Belarusian track and field athlete Kristina Timanovskaya, who refused to return to Minsk after the team leaders suspended her from competing at the Tokyo Olympics and turned to the police for asylum, is far from the first athlete from the countries of the former USSR to act in a similar way. Back in the days of the Soviet Union, several Russian athletes, including world-class stars, were able to flee to the West, causing a massive scandal in their homeland. Someone was not satisfied with life under the constant supervision of special services, someone wanted great material benefits, and someone was sure that their career would be better in the West, where the authorities would not interfere with it.

Present Time recalls the loudest stories of sports escapes from the USSR (and Russia) and tells how the fate of the people who did it happened.

Ludmila Belousova and Oleg Protopopov, figure skating

Belousova and Protopopov were champions in figure skating at the Olympics in 1964 and 1968, world and European champions 1965-1968, champions of the USSR 1962-1964 and 1966-1968, and one of the most famous athletes of the 1960s and 70s. They fled to the West in 1979: they stayed in Switzerland during the tour. At that time, Protopopov was already 47, Belousova – 44. They were not active members of the team, but were soloists of the Leningrad Ballet on Ice, whose fame also thundered around the world.

The athletes, in their own words, did not think about escaping for a long time, but everything changed when they were not allowed into their third Olympics:

“They didn’t think to take us anywhere,” Oleg recalled in the book “Unsurpassed”. “They said about us that if we win the third Olympic Games, we will stay abroad. At that time there were no grounds for this. I don’t know who did it but at the time, to say that was the meanest low blow.

The reasons for emigration, according to the skaters, were purely creative: the couple emphasized that they only needed ice and the opportunity to skate, which they are deprived of in the USSR because of their age:

“In ballet on ice, I felt depressed, humiliated. I was poked all the time, pressed down all the time. Therefore, we decided: there will be an opportunity – we have nothing to do there,” Belousova admitted in an interview.

Behind the Iron Curtain in a hot air balloon. Watch a film about how the Czechoslovak cycling champion fled from socialism

After their escape, a deafening scandal erupted in the USSR, and the references to Belousova and Protopopov even disappeared from sports reference books. The echo of this scandal spoke for decades. For example, when Belousov and Protopopov invited Belugari at the Olympics in Kalgary in 1988 to speak for demonstrations, the Soviet delegation threatened that the USSR team in this case would boycott the closure ceremony.

“My sister and her husband especially went. He worked in the State Bank and was the chief engineer of some department-his bet was immediately reduced to half. It was very difficult for the family,” Belousova recalled.

Victor Korchny, chess

The famous Soviet chess player and multiple champion of the USSR, Viktor Korchnoi, became a defector in 1976 – after international competitions in Amsterdam, he refused to return to the USSR and decided to stay in the West. He was 47 years old. And although he was not the first chess player who fled from the USSR (Alexander Alekhin did the first in 1921), his decision also led to a huge scandal.

“There are many people who consider me a dissident, they think that I fought for the collapse of the Soviet Union. Probably, this cannot be completely denied,” said Korchny in an interview. “The Soviet authorities imposed a war on me, and in this confrontation I held a“ dissident ”position . I had to flee from the USSR due to the fact that my chess life was in danger.

The Korchny family remained in the USSR, and after that his relatives had big problems – especially his son. As in the case of Belousova and Protopopov, a campaign was deployed in the USSR to discredit the athlete, and his name was ceased to be mentioned in sports news. When Korchny defeated the candidates for the chess crown in the match and his match was prepared with Anatoly Karpov, in the news he was simply called the contender.

After the escape of Korchny, he lived in Switzerland, where, after the collapse of the USSR, his son also moved. The citizenship of the USSR and the title of master of sports were deprived of him, but returned after the collapse of the USSR.

Stanislav Kurilov jumped off the cruise liner and sailed 100 kilometers to escape from the USSR. How it was

In addition to Korchny, several more chess players fled from the USSR:

- Odessa Lev Alburt asked for political asylum in 1979 at the Chess Champions Cup in the Germany. After that, he played for the US national team;

- The chess player from Uzbekistan Igor Ivanov in 1980 escaped from an airplane on a transplant in Canada, returning from the tournament in Cuba, and also asked for political asylum. But the career of both athletes after the escape was much less bright than that of Korchno.

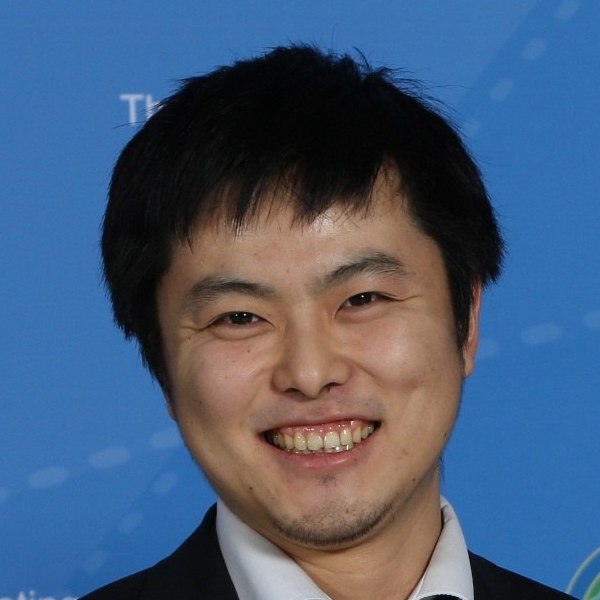

Gata Kamsky, chess

Perhaps the most famous chess shoot after the escape of Korchny was the non -return in 1989 in the USSR of the chess Wunderkind, chess player Gata Kamsky (real name Gataulla Sabirov). After one of the tournaments in New York, his father Rustam Kamsky, a master of sports in boxing, decided to stay with his son in the United States.

Kamsky in an interview emphasized that he himself did not make a decision on the escape: his father decided everything for him.

“I was 14 years old then. Dad decided everything for me, he planned this step in advance. In 1988, we played in the youth championship, and my father planned to meet with representatives of the American Chess Federation to get their invitation. Even then, my father planned the escape to the west, ”he explained.“ We contacted the FBI. In the end, on the last day of the tournament in New York, people from the FBI entered the hall and, when my game ended, took me and my father to our hotel room and my father and my father and my father They cordoned off him. Then they plunged us and our things into the van and took us to the main building of the FBI in New York. After that, the father was subjected to long interrogation, in which three or four people took part. My dad has talent and describe events so, so, describes so, To involve people. In general, he drew all this for them so that they provided us with political asylum.

Kamsky later admitted that his escape was organized not because the athlete was allegedly persecuted in his homeland for being a Tatar, and in order to push his career: in a chess team in the United States there were much fewer competitors than in USSR national team.

My father managed to explain that I can bring America the title of world chess champion. There was always a problem in the Soviet Union in the Soviet Union. There have always been a lot of phenomenal talents, and despite the fact that I won the Russian championship among juniors, I did not succeed in To visit international competitions, ”said Kamsky.“ All decisions in this area were made by the State Sports Committee in chess. It was they who decided the fate of chess players. If for any reason you did not like it, they could completely put an end to your talent. Dad understood, That it will be hard to fight with him.

In 1991, Kamsky became the US champion and achieved the right to play with Anatoly Karpov a match for the world championship under the auspices of FIDE. He lost the match, and after that his career was declining.

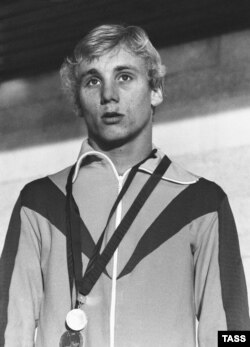

Sergey German, jumping in water

The jump in the water Sergey Germansov, one of the main contenders for winning in jumping from the tower, tried to run to the west during the Olympics in Montreal in 1976. But at that time he was only 17 and a half years old, and the Soviet special services were able to protest the escape – Canada gave refuge from only 18 years old.

After escaping the athlete, his native grandmother turned to the athlete, who raised an athlete in Frunze (now Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan), and then in Almaty. The woman raised Sergei alone (his father served as a pilot in a grouping of Soviet troops in Hungary, and his mother could not deal with a child). She asked the Germans not to leave her alone and return to the country. As a result, after three weeks, the athlete still returned to the USSR.

The condition of the Return of the Germans home, the Canadian authorities made a demand that any sanctions were not applied to the athlete.This promise was kept: Nemtsanov graduated from the institute, and in 1979 he won the USSR championship and made it to the Olympic team. But after that, his career actually ended due to problems with alcohol. Many years later, Nemtsanov nevertheless left with his family for the United States: his son Denis was invited to study there, who also became a diver.

Vladas Chesiunas, rowing

The 1972 Olympic champion in canoeing, multiple champion of the USSR, fled Lithuania in 1979, already being a coach. He left for German Duisburg, asking for political asylum in Germany. But the KGB carried out a special operation to kidnap the athlete – and Chesiunas was returned to his homeland.

The Soviet press later stated that Chesiunas allegedly did not intend to flee the USSR, but got into a dubious company, and then returned voluntarily. But in Germany they insisted that the athlete was abducted by the Soviet special services. In a 2002 telephone interview with the Los Angeles Times, Česiunas said he had returned from West Germany voluntarily but was threatened with jail time by the Soviet authorities for his desertion. And in 2018, in another interview, the athlete said: “I returned home of my own free will. But if I knew how hard it would be for me later in the USSR, I would have stayed in West Germany. I went to the KGB for three months as a job, wrote explanatory notes, gave evidence. The tension was such that I went to the hospital.

Alexander Mogilny, hockey

The famous Soviet hockey player fled to the West on May 1, 1989, immediately after the end of the World Championship in Stockholm: he asked for political asylum in the United States. Later it turned out that the athlete's escape was not made for political reasons: he was prepared by the scouts of the Buffalo Sabers hockey team, with whom he signed a contract.

Twenty-two years after escaping to the United States, Mogilny, in an interview with Sport-Express, noted that he left Moscow as a poor man and did it for economic reasons:

“I left Moscow as a beggar. I was a natural beggar! I was an Olympic champion, world champion, three-time champion of the USSR. At the same time, I didn’t even have a meter of housing. Who needs such a life? And these diplomas with medals?” he said frankly.

Swimming from the USSR: Pyotr Patrushev in 1962 swam 35 km across the Black Sea from Batumi to Turkey

In the NHL, Mogilny had an impressive career. He is one of five Russian hockey players who have scored more than 1000 points in his career, and also the first Russian hockey player to become the captain of the NHL team.

Sergei Fedorov, hockey

World hockey champion in the USSR national team in 1989 and 1990 Sergei Fedorov disappeared from the camp of the USSR national team in the summer of 1990 on the eve of the Goodwill Games in Seattle (USA). He soon began playing for the NHL club Detroit Red Wings.

Given the fact that his escape took place in the 90s, Fedorov was not deprived of citizenship, which is why a year later he played brilliantly for the USSR national team at the World Cup, and then at other competitions. Fedorov, like Mogilny, said that the reasons for his escape were economic: the NHL paid completely different money.With Detroit, Fedorov won the Stanley Cup three times and became the first European to win the NHL regular season MVP award. He finished his career only in 2012.

Julia Stepanova, running

Russian runner Yulia Rusanova fled Russia already in the 2010s, and also with a big scandal. This happened after she, along with her husband Vitaly Stepanov, a former employee of the Russian Anti-Doping Agency (RUSADA), became an informant for the World Anti-Doping Agency WADA and spoke about the massive doping program in Russian athletics.

Stepanova herself used doping for a long time (testosterone injections, anabolic steroids and erythropoietin) at the suggestion of her coach Vladimir Mokhnev, and RUSADA employees covered her up and made sure that her tests at international competitions were clean. However, in 2013, the athlete was still caught and disqualified. After that, Stepanova and her husband became WADA informants and recorded conversations about the doping program with coaches, athletes and doctors.